Measuring the ‘working length’ for root canal file use.

Determining a canal’s proper working length.

As we explain in our outline of the root canal procedure The steps., it’s important for a dentist to clean the entire length of each root canal they treat. But it’s also just as important that they don’t use their files beyond this point (beyond the tip of the tooth’s root).

This page explains how a dentist makes that calculation. How they measure the proper “working length” of a canal.

Taking root canal length measurements.

There are two primary methods that a dentist typically relies on to make working length calculations.

The old …

One of them is the traditional method of positioning a root canal file in the canal, and then taking an x-ray picture of it. (The first use of this method actually dates all of the way back to 1899. [Ingle])

… and the newer.

The other involves the use of a device called an “electronic apex locator” (EAL). (The term “apex” in this context refers to the tip of a tooth’s root.)

While EAL’s were first introduced into clinical practice around 50 years ago, these types of units have only been in widespread usage in dental offices since the 1990s.

Newer isn’t necessarily better.

It’s interesting to note that the development of electronic devices hasn’t supplanted the need for the continued use of the traditional method of taking an x-ray.

An influential study by Martinez-Lozano (2001) that compared dentists’ ability to interpret the findings of both methods concluded that neither was completely satisfactory in aiding them in determining a canal’s true working length.

▲ Section references – Ingle, Martinez-Lozano, Hargreaves

A) Making working length calculations via the use of x-rays.

Background.

This method simply capitalizes on the fact that metal objects are easily visualized on dental radiographs.

(Dense metal objects block the passage of x-rays. That means that the portion of the film/detector that lies opposite the object won’t be exposed/triggered. As a result, the outline of the metal object will appear white in color on the x-ray picture.)

How a dentist takes a measurement.

(The measurement process can only take place after your dentist has gained direct access to the interior of your tooth and the openings of its root canals. Per our outline of the root canal process (see link above), that involves completing Steps 1 through 3.)

The measurement process.

X-ray of a tooth with a file in place.

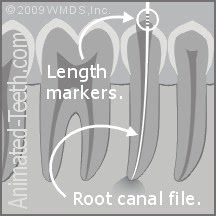

- Your dentist will tease a root canal file More about these instruments. (see picture below) into the tooth’s root canal, to a point they anticipate approximates the root’s (canal’s) end.

(Your dentist has a number of ways by which they can estimate this length. They may take a measurement directly from a previously taken x-ray, use the “standard” canal length suggested by anatomical studies of teeth, or simply by the way the file feels (tactile discovery) as they work it inside the canal.)

- With the file positioned, they’ll then take an x-ray of the tooth.

- The picture will reveal if the root canal file has been positioned properly. (With it either extending all of the way to the tip of the tooth’s root, or whatever near root-tip position the dentist feels is appropriate. Dentists debate what’s best.)

A = The metal portion of a file.

B = Measurement markings.

- The actual length measurement is read right from the root canal file, from its measurement markings. (These calibration points are labeled “B” in our picture.)

(Different than shown in our illustration above, the markings are read on the file after it has been withdrawn from the tooth. The marks themselves don’t actually show on the x-ray picture.)

(Technically, the only purpose of taking the x-ray is to document that point to which the file reaches inside the tooth. However, being able to actually visualize this relationship, as well as visualize and examine other aspects of the tooth itself, offers the dentist a wealth of information.)

The stopper is positioned over the corresponding file marker.

- The dentist will know which marking applies to the measurement because they will have slipped the file’s rubber stopper (labeled “C” in our picture above) to the appropriate corresponding point once the file has been positioned inside the tooth.

Our picture here illustrates this point.

- These same steps are repeated to establish the working length for any other canals the tooth may have. (Teeth frequently have several canals and/or roots. What’s normal? | Variations.)

(If the dentist finds that the act of inserting multiple files inside a tooth at the same time is physically possible (which it frequently is), they may be able to establish the working length of multiple canals via the same x-ray.)

What if the x-ray shows that the file hasn’t been positioned perfectly?

You may be wondering what happens in the case where the dentist’s initial estimate was wrong and the file doesn’t extend to the canal’s end.

- The dentist may feel that based on the x-ray picture they can accurately just estimate the amount of adjustment that’s needed in the length measurement.

- Between what they see on the x-ray, and the way the file feels to their fingers as they work it in the canal, they may feel that they can determine the proper length on their own. (A canal typically has a terminal constriction that can be felt.)

- They may recalibrate the file and confirm this measurement via the use of an electronic apex locator (discussed below).

- Or if they feel it’s necessary, they can reposition the file to their next best estimate (based on what’s seen on the first x-ray) and simply take another one for confirmation.

What’s this process like?

Overall, the whole process of establishing a canal’s working length via the use of an x-ray should be a minimal event for you.

This process is performed well into your tooth’s root canal procedure, and long after you’ve been numbed up. So feeling something (like the file being positioned) won’t be an issue.

The act of taking the x-ray isn’t necessarily a quick process. Your dentist will first need to loosen the rubber dam What’s this? that’s been placed for your procedure, position the x-ray film/detector next to your tooth (you’ll probably be asked to hold it in place with your finger), snap the picture, and then reconfigure the rubber dam.

The process of disassembling the dam for x-ray placement has some potential consequences (we discuss them below). In comparison, taking an electronic measurement (also explained below) is much quicker, does not require dental dam disassembly, and requires no participation on your part.

B) Taking electronic root canal working length measurements.

In recent decades, the use of electronic length-measuring devices has become commonplace. These units are referred to as “electronic apex locators,” or just EAL’s. (The word “apex” refers to the tip of the tooth’s root.)

Background.

Since the 1960s, EAL’s have taken various forms, with each next-generation unit typically relying on similar, yet more advanced, electronic circuitry.

(For example, progressing from just measuring resistance to impedance. Also, newer designs overcome issues such as the presence of tissue, blood or other liquids in the canal (all are conductors of electricity). [Ingle – linked above.])

How a dentist takes a working length measurement using an electronic apex locator.

While how any specific type of unit might be used may vary, our description here explains how they are generally used.

(The measurement process can only be performed after your dentist has gained direct access to the interior of your tooth and its root canal system. Per our outline of the root canal process (see link above), that involves completing Steps 1 through 3.)

- Your dentist will first place a root canal file into the tooth’s root canal, to a point where it still lies short of the canal’s end.

(Your dentist has a number of ways by which they can estimate this length. They may take a measurement directly from a previously taken x-ray, or base their decision on what is the “standard” canal length as suggested by anatomical studies.)

Root canal files.

A = Metal shaft.

B = Measurement markings.

- They’ll then clip one of the EAL unit’s wire leads on some exposed aspect of the file’s metal shaft (labeled “A” in our picture).

They’ll also gently tuck its second lead (wire) against the inside of your lip. (This metal-to-tissue contact completes the electrical circuit that the unit requires).

- With all of the leads positioned, they’ll then begin to slide the file slowly on into the canal. As they do, the EAL will measure changes in the (very low level) electrical current emitted and detected by the unit.

(As the metal file comes closer and closer to the conducting tissues that surround the tooth’s root, the nature of the current will change in ways that can be interpreted by the unit.)

A digital readout, light indicator and/or beeping sound will keep the dentist posted in real-time about how close the file currently is to the canal’s end (e.g. 1.5, 1.0, 0.5 or 0.0 mm from the root’s end).

- Once the chosen end position has been reached Per their discretion., the length measurement is read from the calibration markings on the file (labeled “B” in our picture above). (The electronic unit only indicates how close the file’s tip is to the end of the canal, not the actual file length measurement.)

- A separate measurement will need to be made for each of the tooth’s individual root canals. However, this can be expected to be accomplished quite simply and quickly. (The whole process described here should be able to be completed in around a minute or so.)

What’s this step like?

Despite the fact that an apex locator is an electrical unit, its use is a non-event for the patient. You won’t feel a thing. And, in fact, using one is a plus because it typically makes performing your procedure quicker and simpler.

- When an x-ray measurement is taken, the dentist has to disassemble the rubber dam (so to gain access to your mouth), place the film or x-ray sensor next to your tooth, take the picture, and then put everything back together again.

- In comparison, when an electronic unit is used, minimal preparation is required. A measurement can usually be taken in less than a minute, and smoothly incorporated into the dentist’s working routine.

The use of both methods is generally/usually the best plan.

Having an electronic apex locator available doesn’t mean that the technique of determining a canal’s working length via x-ray isn’t needed or shouldn’t be performed.

- Using both techniques, and evaluating and comparing their results, has been shown to result in greater accuracy. (Ingle – linked above.)

- Just as important, an x-ray may reveal essential anatomic information about the tooth and its configuration that could never be identified by electronic measurement alone.

For these reasons, expect your dentist to use a combination of both methods.

Update: Issues associated with the COVID-19 pandemic.

Since originally writing this page, the COVID-19 pandemic has become an issue worldwide. And that fact is transforming the way dentistry is practiced. (Not just from the standpoint of COVID-19 but also with the possibility of future pandemics in mind.)

Electronic vs. x-ray apex determination.

In regard to the issue of root canal length measurement, it must be pointed out that a great advantage of determining this value electronically is that this technique is performed under the isolation of a rubber dam. (The method that dentists use to prevent oral fluids from contaminating a dental procedure’s work environment.)

In comparison, when an x-ray is taken, the tooth’s dam must be partially disassembled so the x-ray film or detector can be positioned inside the patient’s mouth. Unfortunately, this process creates an exposure of the dental office environment and staff to the patient’s potentially infected saliva and oral aerosols (like those created by coughing).

By no means does this mean that radiographic apex determination should not be used for cases. But the added exposure taking x-rays creates to patient oral fluids will no doubt encourage your dentist to lean toward the use of an electronic apex locator whenever possible.

Page references sources:

Hargreaves KM, et al. Cohen’s Pathway of the pulp. Chapter: Instruments, materials and devices.

Ingle JI, et al. Ingle’s Endodontics. Chapter: Diagnostic Imaging

Martinez-Lozano MA, et al. Methodological considerations in the determination of working length.

All reference sources for topic Root Canals.