What do cavities look like on dental x-rays?

How dentists identify cavities on x-rays.

A common scenario.

You’re at your dentist’s office for a checkup. Radiographs (the formal term for x-ray pictures) have been taken of your teeth and you’ve just been told the bad news, you have a cavity.

Your dentist shares the pictures of your teeth with you, so you’ll be fully informed. But the problem is, you don’t really know what you’re looking at or what to look for.

Interpreting dental x-rays isn’t all that hard.

We can’t make you an expert but after reading this page you’ll have some firm insight into how dentists identify tooth decay on dental radiographs (x-rays).

Dentin and Enamel: The calcified tissues of a tooth.

Identifying tooth decay on dental x-rays.

How dental x-rays work.

The basic premise involved is this …

More details.

When a dentist takes a radiograph, a tooth’s hard mineralized tissues will block some of the radiation (x-rays) that have been aimed through them.

Due to this effect, those portions of the x-ray film (or digital image receptor, the more modern way to take an x-ray), that lie behind these heavily calcified tissues will be less exposed (have fewer x-rays hit them).

As a result, these protected portions of the picture will look lighter in color. (These areas of the film don’t turn as dark because fewer x-rays were able to penetrate through the tooth to strike them.)

On x-rays, more calcified tooth structures appear lighter in color.

Animation of the progression of tooth decay (see below).

On an x-ray (see illustration):

- The enamel outer covering of a tooth shows the lightest color. That’s because it has a higher mineral content than the other parts.

- In comparison, the dentin layer (a less calcified tissue) has a somewhat darker appearance on the film.

- The outline of the hollow space inside a tooth (it’s pulp chamber, the location where its nerve tissue resides), gives the darkest appearance.

That’s because in that region much of the thickness of the tooth is comprised of non-calcified soft tissue, thus a higher percentage of x-rays are able to pass through that region and expose the film.

Why cavities show up on x-rays.

Since decay is an area of tooth demineralization (an area of reduced mineral content), or even possibly an outright hole (a space that would have no mineral content at all), those locations where it has formed will show as a darkened area on an x-ray.

That’s because the decayed portion of the tooth is less “hard” (less dense or intact) and therefore the x-rays penetrate that portion of the tooth more easily and ultimately expose the film more so (making the corresponding area on the film look darker).

- The tip-off to the dentist that a problem exists is that the dark area on the picture involves a location or aspect of the tooth that in health wouldn’t be expected to be less dense (have reduced mineral content).

- And characteristically, there are certain areas on a tooth that are more prone to decay formation than others (like right in the region of contact between two teeth). So if the dark spot corresponds with that type of location, it is especially telling.

Stages of cavity formation that show up on x-rays.

Our mockup of a dental x-ray illustrates some of the stages that the decay process goes through.

The characteristic look of advancing tooth decay on dental x-rays.

- Frame A: This frame illustrates the earliest stage of tooth decay formation that shows up on a dental x-ray.

Notice how there’s just ever so slightly a darkened area in the enamel portion of the tooth right exactly where it touches its neighbor (the contact point). That’s the decay. (This person has not been flossing enough.)

Most dentists won’t recommend placing a filling until the x-ray shows that the decay has completely penetrated the enamel layer of the tooth (as shown in Frame B). The lesion shown in Frame A may not progress further if this person starts to floss.

- Frame B: Once the x-ray image shows that the decay has penetrated through the tooth’s enamel layer and into dentin, a dentist will typically recommend placing a filling (see discussion below).

Real-life examples of the carious lesions illustrated in Frames A, B and C.

- Frame C: As mentioned above, the dentin portion of a tooth is less mineralized (less “hard”) than a tooth’s enamel layer. And because of this, it will decay at a faster rate.

This phenomenon shows up on x-rays. Notice how in Frame C the lesion in the enamel layer has only slightly increased in size while the decay in the dentin portion of the tooth has advanced significantly.

It’s especially important to tend to a lesion like this promptly, before it has a chance to spread enough that it significantly compromises the structural integrity of the tooth or damages its nerve.

- Frame D: Frame D illustrates one worst-case scenario situation.

If a developing cavity is left untreated, it can advance all the way to the tooth’s nerve tissue. If it does, not only must the decay be removed and the damaged tooth structure repaired but additionally the tooth will require root canal treatment.

Clearly, the early treatment of tooth decay (preferably at the point shown in Frame B) is a case where a stitch in time saves nine.

▲ Section references – White

Examples – What type of treatment does this x-ray show is needed?

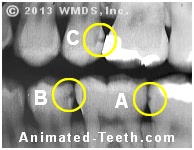

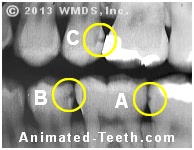

A bitewing dental x-ray.

This film shows two fully formed cavities and one that’s just starting.

- Circle A – The “notch” on the 2nd molar would be classified as a “watch” or incipient lesion.

The fact that some decay has already formed is worrisome. The dentist will need to keep a close eye on this area when future x-rays are taken so to make sure the lesion hasn’t progressed further.

Treatment involving some type of preventive measure to deter further progress is indicated. (This might involve: topical fluoride applications, applications of amorphous and reactive calcium phosphate complexes, the use of synthetic hydroxyapatite in an acid paste to repair the defect.)

- Circles B and C – The extent of the decay process in these areas has clearly penetrated the enamel layer of the tooth. And due to this fact, the underlying dentin aspect of the tooth is now clearly involved too.

Historically, these types of lesions were considered full-fledged cavities, and as such an indication for filling placement. Nowadays, techniques like resin infiltration might be used in an attempt to arrest the progress of these lesions instead. If so, future monitoring with x-rays will be needed.

- FYI – The very white objects on this radiograph are existing metal (amalgam) dental fillings. They appear as bright white because the filling’s metal is so dense that few if any x-rays have been able to penetrate it and expose the x-ray film/sensor.

“Bitewing” x-rays – Why are they used to search for decay?

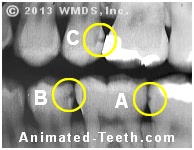

The film shown here is the same radiograph as above. In dental terminology, it’s referred to as a “bitewing” x-ray. This is the standard type of image that’s used to look for cavities.

A bitewing dental x-ray showing 3 areas of decay.

- The name “bitewing” comes from the fact that the patient bites on a tab (a single “wing”) attached to the film or digital sensor. This holds it in place and still while the picture is taken.

- Bitewings are the only type of routine intraoral dental x-ray that shows both the upper and lower teeth. (“Intraoral” means the film or sensor is placed inside your mouth when the image is taken.)

- The intention is to show the crowns of the teeth (the portion of each tooth that extends past the gum line), as well as the crest of the jawbone that surrounds and holds them in place.

(In regard to cavity detection, when this is accomplished the picture shows the full extent of each tooth on which it’s possible for decay to start.)

- A primary purpose of taking bitewing x-rays is to detect cavity formation in the general area of the point of contact between two teeth.

(This is a location that can’t be directly visualized by the dentist, and is often difficult or impossible for them to fully examine clinically. As such, taking bitewing x-rays may be the only method available to adequately evaluate this region.)

- When taken, the goal of the technician is to “split the contacts” for the picture. This refers to getting everything lined up so the contact point between all adjacent teeth can be clearly seen.

(In cases where the x-ray machine isn’t lined up correctly, the teeth will look overlapped. That makes reading the x-ray much more difficult, if not impossible. For example, minute changes like those in circle A in our picture above might not be detected at all.

▲ Section references – White, Foster-Page

How often should you have bitewing x-rays taken?

Taking x-rays shouldn’t just be a perpetual, automatic profit center for your dentist. They should instead be taken for specific reasons.

The authority.

Fortunately, via a collaboration of representatives from the American Dental Association (ADA) and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), a set of guidelines exist for dentists to follow. They’re titled: “Dental Radiographic Examinations: Recommendations for Patient Selection and Limiting Radiation Exposure.”

What are the guidelines for taking bitewing x-rays as a tool for detecting tooth decay?

- The age of the patient, or more specifically, what type of teeth the person currently has. (Just primary (baby) teeth, a mix of permanent and primary teeth, or just permanent ones.)

- What previous x-ray pictures exist and the access the person’s current dentist has to them.

- What’s been seen during the patient’s current oral examination.

- The patient’s dental history, including their historic experience with decay and the extent of dental work that they’ve required.

How often should you have bitewings taken? – Common guidelines.

1) Adult recall patients.

The term “recall” as used in this context refers to a dental appointment where the patient has returned for periodic examination (a dental “checkup”). An interval of every 6 to 12 months is common.

Bitewings every 24 to 36 months. – If no decay is identified during the patient’s clinical examination, and they’re not considered to have any associated factors that place them at increased risk for developing cavities.

Bitewings every 6 to 18 months. – If clinical examination identifies decay, or the patient is considered to have associated factors that place them at increased risk for developing cavities.

2) Adult new patients.

“New” patients are those persons new to a dental practice and therefore the dentist has limited knowledge about the person’s decay history and has no historic x-rays as background information.

Taking bitewings is generally indicated. – Especially in the case where decay has been identified during the patient’s clinical examination.

3) Adolescent recall patients – Permanent dentition only.

This category is composed of adolescents that have lost all of their primary (baby) teeth.

The term “recall” as used in this context refers to a dental appointment where the patient has returned for periodic examination (a dental “checkup”). An interval of every 6 to 12 months is common.

Bitewings every 18 to 36 months. – If no decay is identified during the patient’s clinical examination, and they’re not considered to have any associated factors that place them at increased risk for developing cavities.

Bitewings every 6 to 12 months. – If clinical examination identifies decay, or the patient is considered to have associated factors that place them at increased risk for developing cavities.

4) Adolescent new patients – Permanent teeth only.

Taking bitewings is generally indicated. – Especially in the case where decay has been identified during the patient’s clinical examination.

5) Adolescent recall patients – Transitional dentition.

The term “transitional dentition” indicates that the person has some permanent teeth but still retains some primary teeth too.

The term “recall” as used in this context refers to a dental appointment where the patient has returned for periodic examination (a dental “checkup”). An interval of every 6 to 12 months is common.

Bitewings every 12 to 24 months. – If no decay is identified during the patient’s clinical examination, and they’re not considered to have any associated factors that place them at increased risk for developing cavities.

Bitewings every 6 to 12 months. – If clinical examination identifies decay, or the patient is considered to have associated factors that place them at increased risk for developing cavities.

6) Adolescent new patients – Transitional dentition.

Taking bitewings is generally indicated. – Especially in the case where decay has been identified during the patient’s clinical examination.

7) Child recall patients – Primary teeth only.

This group of children is characterized by the fact that they only have primary (baby) teeth. Note: Some children have spaces between all of their baby teeth. If so, x-rays are not needed to evaluate for decay.

The term “recall” as used in this context refers to a dental appointment where the patient has returned for periodic examination (a dental “checkup”). An interval of every 6 to 12 months is common.

Bitewings every 12 to 24 months. – If no decay is identified during the patient’s clinical examination, and they’re not considered to have any associated factors that place them at increased risk for developing cavities.

Bitewings every 6 to 12 months. – If clinical examination identifies decay, or the patient is considered to have associated factors that place them at increased risk for developing cavities.

8) Child new patients – Primary teeth only.

Taking bitewings is generally indicated. – Especially in the case where decay has been identified during the patient’s clinical examination.

Page references sources:

Am. Dental Assoc. and US FDA. Dental Radiographic Examinations: Recommendations for Patient Selection and Limiting Radiation Exposure.

Foster-Page LA, et al. The effect of bitewing radiography on estimates of dental caries experience among children differs according to their disease experience.

Hilton TJ, et al. Summitt’s Fundamentals of Operative Dentistry: A contemporary approach.

White SC, et al. Oral Radiology: Principles and Interpretation.

All reference sources for topic Tooth Decay.